Guidelines

-

Canadian evidence-based checklist [2] for Syrian refugees by the CCIRH

-

Caring for a newly arrived Syrian refugee family [3] by Kevin Pottie et al in CMAJ

-

Newcomer Clinical Care Pathway [4] by Interior Health

-

Caring for Kids New to Canada [5] by the Canadian Pediatric Society

-

The Canadian Guidelines for Immigrant Health [6] in CMAJ

Trauma / Mental Health

Interpretation

-

Translated patient handouts in Arabic [9].

Settlement

-

ISSofBC Refugee Readiness Hub [10]

Backgrounders

-

Population Profile: Syrian Refugees [11] by Citizenship and Immigration Canada

-

Health Status of Syrian Refugees [12] by the Public Health Agency of Canada

-

Culture, Context and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Syrians [13] by the UNHCR

-

Enhancing Access to Prevention and Health Care for Syrian Refugees in Jordan [14] by the International Organization for Migration

-

Syrian Refugee and Affected Host Population Health Access Survey in Lebanon [15] by Johns Hopkins University

-

Nutritional Status of Women and Child Refugees from Syria - Jordan, April - May 2014 [16] by Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

-

Impact of and response to increased tuberculosis prevalence among Syrian refugees compared with Jordanian tuberculosis prevalence: case study of a tuberculosis public health strategy [17] by Conflict and Health

-

Health care providers' handbook on Muslim patients [18] by Queensland Health

Other Resources

-

Dentists [20] in Vancouver, Richmond, North Shore and Surrey who accept IFH, some of whom speak Arabic, provided by the BC Dental Association.

-

Canadian Medical Association [21]

-

The College of Family Physicians of Canada [22]

-

Doctors of BC [23]

-

Interior Health [24] Newcomer and Refugee Care

BC Refugee Readiness Fund is part of the WelcomeBC

umbrella of services, made possible through funding

from the Province of British Columbia.

Political Context

By: Yasmeen Mansoor and Sujin Im (BSc.), MD Candidates, Class of 2019, University of British Columbia

Background

The conflict in Syria began in early 2011 within the context of Arab Spring, a series of pro-democracy protests and uprisings in the Middle East. It began when residents of a small southern city took to the streets to protest the torture of students who had put up anti-government graffiti. President Assad’s government responded with heavy-handed force, and demonstrations for democracy quickly spread across much of the country. But since then, the Syrian civil war has morphed into a multifaceted conflict with many moving parts, beyond the tensions between rebel and government forces. The armed conflict now involves government forces, competing rebel groups, international powers, jihadist groups and the Islamic State.

As Syria enters its fifth year of conflict, frontlines continue to shift and high levels of insecurity, violence and destruction of infrastructure continue to restrict humanitarian access. The delivery of basic services in many parts of the country has also been affected. According to estimates by the UNHCR in 2015, the conflict has killed over 250,000 people and displaced over 11.9 million people (more than half of its population), making the situation in Syria the largest humanitarian crisis worldwide.

(Source: UNHCR-Country Profile, CIA)

Displacement in the Syrian Conflict

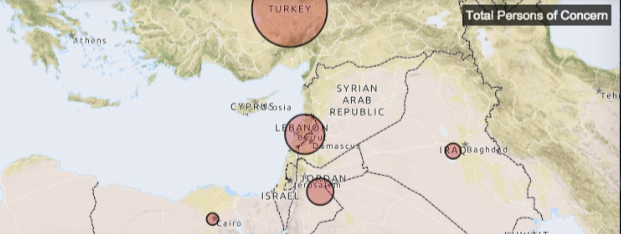

In 2015, the number of people displaced in Syria reached 11.9 million. This includes 7.6 million people that remain inside Syria and 4.1 million registered refugees who have fled to neighboring countries. The majority of refugees reside in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt. The asylum countries are illustrated in the figure below. However, there are growing concerns about the ability of neighboring countries to support the increasing influx of Syrian refugees.

Figure and Numbers from UNHCR-Refugee Response

- Turkey: 2,291,900 (updated 10 Dec 2015)

- Lebanon: 1,070,189 (updated 30 Nov 2015)

- Jordan: 633,466 (updated 17 Dec 2015)

- Iraq: 244,527 (updated 28 Nov 2015)

- Egypt: 123,585 (updated 30 Nov 2015)

Canada’s Commitment to Resettlement of Syrian Refugees

Efforts to resettle or admit refugees have been initiated by various countries. As of December 2015, thirty countries, including Canada, have pledged [25] to accept a total of 125,650 Syrian refugees.

Canada resettled 3089 Syrian refugees between January 1, 2014 and November 3, 2015. In November 2015, the Government of Canada announced that it would resettle 25,000 additional Syrian refugees by the end of February 2016. Since then, 7671 Syria n refugees have arrived in Canada, as of January 7, 2016. The remaining arrivals are planned for January and February 2016.

Cultural and Demographic Context

By: Yasmeen Mansoor and Sujin Im (BSc.), MD Candidates, Class of 2019, University of British Columbia

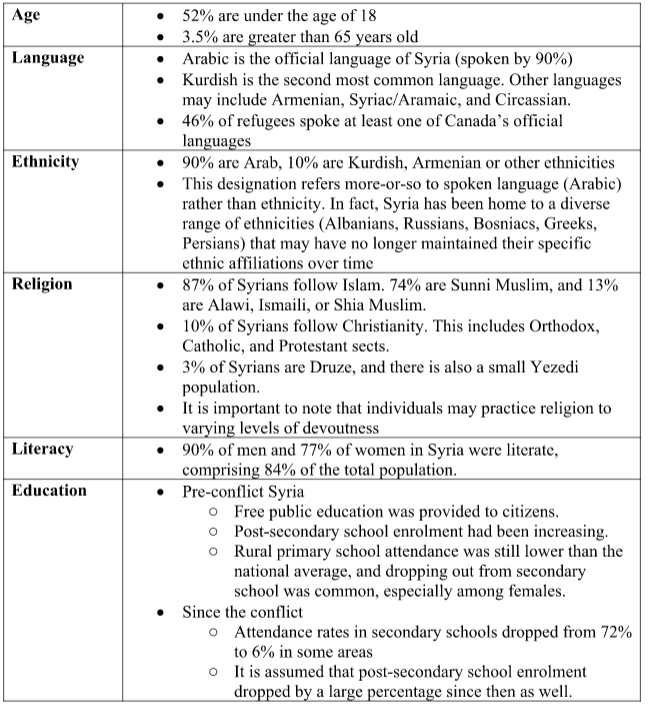

Some general demographic information regarding the Syrian refugee population has been summarized below (Source: CIC):

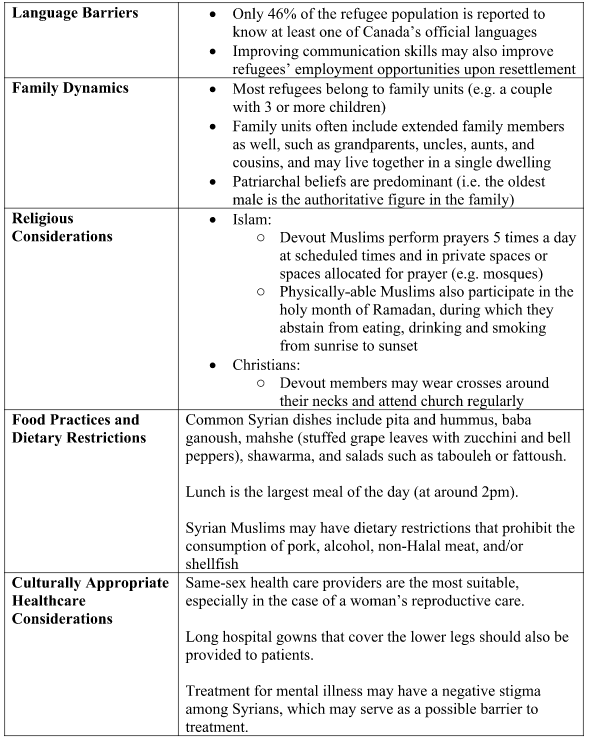

Cultural Considerations in Providing Care to Syrian Refugees (Source: CIC)

Health Context

By: Yasmeen Mansoor and Sujin Im (BSc.), MD Candidates, Class of 2019, University of British Columbia

Prior to the conflict, Syria was a lower middle-income country with a relatively young population. 90% of the population in the country had access to clean water and sanitation at the time, and vaccination coverage was estimated at 90%. Infectious disease rates in the country had been low compared to higher-burden countries (Source: WHO).

Since the conflict in 2011, displaced Syrian refugees faced issues such as limited access to food and clean water, limited protection from extreme weather, unsanitary and overcrowded environments, and limited access to vaccinations. These factors have increased their chances for certain illnesses (Source: PHAC). Below is a list of some health concerns to be aware of in the Syrian refugee population.

Immunization

- Immunization records may not be available for most refugees. Age-appropriate vaccinations according to the provincial vaccination schedule, and seasonal influenza vaccines, should be provided if vaccination statuses are uncertain.

- Note that no significant outbreaks or transmission rates of infectious diseases have been reported in countries that have accepted Syrian refugees. As such the refugee population does not pose a health risk to Canadians (Source: PHAC).

Tuberculosis, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV, Strongyloides

- Refer to the CMAJ article Caring for a newly arrived Syrian refugee family [3] for evidence-based recommendations regarding screening and treatment for the above infections

Injuries and Disabilities

- Injuries: 5% of health care consultations in Jordan and 1% in Lebanon were for injuries in 2013 (UNHCR-Review). Injuries may be war-related, and may have resulted in physical disability.

- Disabilities: 1 in 10 refugee households in Jordan had at least 1 family member with a disability - 41% are children (UNHCR-Review).

Other Acute Health Issues

- Wound care, issues of malnutrition, and dental health issues may be common in this population (PHAC)

Chronic Illnesses

- Hypertension (7.6%), diabetes (2.2%) and cardiovascular disease (0.9%) were the hree most common chronic diseases detected by the Citizen and Immigration Canada (CIC) during an Immigration Medical Exam in a cohort of Syrian refugees (Source: CIC).

- Refugees may have experienced interruptions in their treatments for chronic illnesses due to conflict and resettlement.

Mental Illness and Trauma

- The most significant clinical problems in populations affected by collective violence and displacement include depression, prolonged grief disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and various forms of anxiety disorders.

- Common traumatic events faced by Syrian refugees may include losing family members, concern about missing family members, being subject to or witnessing violence, suffering from torture, facing indiscriminate bombardment and shelling, losing personal possessions and homes, and facing perpetual uncertainty due to displacement.

- 43% of Syrian refugees were categorized under the Survivor of Violence and/or Torture category in 2013 & 2014 (UNHCR-Review)

- Upon re-integrating into a new society, Syrians may also face a sense of isolation, loss of identity as they integrate themselves in foreign societies, discrimination, financial stress, and stress from seeking supportive environments.

- Management of mental health issues: Symptoms can arise several months after resettlement and thus may require adequate follow up. Non-clinical interventions such as improving living conditions may have more significant impact than psychological or psychiatric interventions.

- Source and additional detailed information on providing mental health care to Syrian refugees: http://www.unhcr.org/55f6b90f9.pdf [13]

Sexual Violence

- Due to underreporting and/or delayed reporting, the prevalence and severity of sexual violence experienced by the Syrian refugee population is unclear

- The act or fear of rape and other forms of sexual violence may have affected women, girls, men or boys in detention facilities, household searches, military raids, checkpoints, and in asylum countries

- Cultural considerations: Refugees may consider speaking about this subject socially unacceptable. In particular, it may be difficult for women to speak about these issues with male family members present.

References for "Political Context," "Cultural and Demographic Context" and "Health Context"

UNHCR-Country Profile: The United Nations Refugee Agency. 2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Syrian Arab Republic. [26]

CIA: Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook – Syria. [27] Date modified: December 10, 2015

CIC: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Population Profile: Syrian Refugees [11]. Published: November 2015

UNHCR-Refugee Response: The United Nations Refugee Agency. Syria Regional Refugee Response [28] – Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal. Date modified: 17 Dec 2015

WHO: World Health Organization. Syrian Arab Republic [29] – Tuberculosis Profile. Modified January 10, 2016

PHAC: Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Status of Syrian Refugees [12]. Accessed: January 7, 2015

UNHCR-Review: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Culture, Context and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Syrians [13]: A Review for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Staff Working with Syrians Affected by Armed Conflict – 2015.

Health Insurance in BC

All Syrian refugees are eligible for Medical Services Plan (MSP [30]) and have full Interim Federal Health (IFH) coverage

MSP

Enrollment in MSP is not automatic. Upon arrival in Canada, refugees must complete this form [31] (usually with the assistance of a settlement worker or sponsor) and send it to Health Insurance BC with copies of immigration documents. There is no wait period for MSP, but processing takes approximately 8-12 weeks. In extenuating circumstances (e.g.. pregnancy), a phone call can expedite the process. Call HIBC with any questions about enrollment.

IFH

Syrian refugees are given their IFH certificate by CBSA officers at the point of entry into Canada, or issued one by an IRCC officer shortly after arrival. IFH is in effect for one year.

As of April 1, 2016, IFH coverage has been fully restored to pre-2012 levels [32], with full coverage for all refugees and claimants, including:

-

Physician and hospital services

[33] -

Laboratory and diagnostic services

[33] -

Medications on BC formulary [34] plus some additional drug benefits [35]

-

Supplemental services [36] such as basic dental care [37], optometry, physiotherapy & counseling

If a patient requires a medication that is not covered, the physician can apply to IFH for Prior Approval [38].

To confirm the patient’s coverage, locate the 8-digit client ID number at the upper right-hand corner of their IFH document, and enter it into Medavie’s secure provider web portal [39].

A patient with IFH coverage (i.e.. for the first year in Canada) is not eligible for Pharmacare, even if they have MSP. A Pharmacare application must be filed at the end of the first year. Refugee patients need to be directed to do this, by their settlement worker, sponsor or primary care provider.

Provider Registration with IFH

Providers (physicians, labs, pharmacies etc) must register with IFH in order to bill for their services. An unregistered health care provider who submits a claim to IFH will have the claim put on hold until they complete the registration.

Providers can register by completing this form [40] and returning it by email, fax or post. There is also the option of registering on the provider’s website [39] by clicking on the “Request Account” link on the top right of the screen. For more detailed instructions on how to register, call Medavie Blue Cross directly.

When a patient with IFH (and no MSP) requires blood work, imaging or a referral, they must be directed to a provider registered with IFH. A provincial list of providers, organized by city, can be found here [41].

Immigration Medical Exam (IME)

The IME for government assisted and privately sponsored refugees is done prior to arrival in Canada. All Syrian refugees destined for Canada have their IME done in Lebanon or Jordan, and are given a paper copy of the results.

The IME consists of a medical history, a focused physical examination and the following investigations:

1. Urinalysis for patients >5y

2. Chest x-ray (posterior-anterior view) to rule out active pulmonary TB for patients >11y

3. Syphilis test for patients >15y

4. HIV test for patients >15y

Historically, Canadian practitioners have been unable to access these results. Only certain results, such as a positive HIV test, are communicated to public health officials in Canada. Rather than assuming that the absence of a notification means a negative screening result, consider repeating the HIV and RPR tests.

Post Arrival Health Assessment

The Canadian Collaboration on Immigrant and Refugee Health has developed Evidence-Based Preventive Care Checklists for New Immigrants and Refugees [42] from different regions of the world. For Syrians, use the Central Middle East checklist [2], available as a printable online checklist or a PDF.

Interior Health has translated a post arrival health assessment nurse screening form [24] into Arabic. It is also available in English, and combined English/Arabic [43].

IFH will pay $94 for a post arrival health assessment (PAHA) [36] and for an interpreter ($29/h x 2h), but the provider must apply for prior approval. The PAHA is usually completed over multiple visits, and divided among team members (e.g. physician and nurse). It ought to include the following:

HISTORY

Current Complaints

Psychosocial

- Family members (who's missing?)

- Country of origin and transit, and dates

- Occupation, education, literacy, housing

Medical and surgical history

Refugee patients rarely arrive with past medical records. The following are common/important issues to identify:

- Neglected chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension

- Injuries (e.g.orthopedic or burn) and disability

- Mental health. Do not ask directly about trauma or torture, but consider using a screening tool.

- Visual and hearing impairment

- Pregnancy and contraception

- For children, failure to thrive and dental issues

Medications and allergies

Often the patient’s chief concern is restarting medications that were discontinued during conflict/transit. To identify foreign medications, contact the Drug Poison Information Centre [44] at 1-866-298-5909. Often medications that refugee patients were taking previously are unavailable in Canada or not covered, and substitutions must be made.

PHYSICAL

- Vital signs

- Visual acuity

- Dental check for painful disease

- Growth for children

- Targeted physical exam based on complaints

SCREENING BLOODWORK

CCIRH-recommended screening is included in the checklists.

Based on the CCIRH Middle East Checklist, and the December 2015 CMAJ article Caring for a newly arrived Syrian refugee family [3], Syrian refugee screening ought to include the following:

Recommended:

- Complete blood count with differential for women of reproductive age and children aged 1-4

- Hep B serology (HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs)

- General age-based preventive screening (e.g.mammography, fecal occult blood testing, diabetes screening)

Consider:

- Varicella serology

- Hepatitis C serology

- Strongyloides serology, given the prevalence of strongyloidiasis in refugee populations and the potential of increased exposure to S. stercoralis in the unsanitary conditions of refugee camps.

- HIV testing if the results from the IME are unavailable, in keeping with the provincial STOP HIV [45] initiative

- Syphilis testing if the results from the IME are unavailable

Not recommended:

- Mantoux testing, as the incidence of tuberculosis in Syria and surrounding countries was below the threshold of 30 per 100 000 population in 2014

- Stool samples for ova and parasites in asymptomatic refugees

VACCINATIONS

If a patient has no documented vaccination history, assume that (s)he has had no vaccinations and follow the provincial immunization ‘catch-up’ schedule [46]. For adults without immunization records use Schedule D. Consider a referral to Public Health.

Trauma and Mental Health

Among Syrian refugees, the most prevalent mental health diagnoses include depression, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), prolonged grief disorder and anxiety disorders.

Over 80% of refugees exposed to trauma recover spontaneously upon reaching safety. Refugee patients’ mental health benefits from attention to basic needs such as shelter, language acquisition and ability to work or attend school.

The CCIRH guidelines recommend against [47] routine screening for trauma and torture, but recommend that clinicians be alert for impaired functioning or high levels of suffering that might be related to PTSD, depression, anxiety or exposure to violence.

The PROTECT Questionnaire [48] was developed by the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims [49] (IRCT) as a tool to identify refugees with trauma-related mental health needs. It consists of ten questions and uses a simple rating scale to predict who is at risk of mental health deterioration, and would benefit from referral and further evaluation.

The Provincial Toll-Free Refugee Mental Health Line [7] is operated by the Vancouver Association for Survivors of Torture (VAST) and provides consultation during working hours to front-line providers (clinical, school and settlement) working with refugees.

IFH covers counseling by a registered clinical psychologist [36] who is an IFH provider, with prior approval. Also consider referral to a community mental health team or psychiatrist.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health [50] (CAMH) has developed the Refugee Mental Health Project [51], an initiative which aims to build providers’ knowledge and skills around refugee mental health through online courses, toolkits and webinars.

More mental health resources are compiled here [8].

BC Refugee Readiness Fund is part of the WelcomeBC

umbrella of services, made possible through funding

from the Province of British Columbia.